Carbon neutrality in 2050: a statistical arrangement that hides the need for sobriety measures

9 min reading

Green growth to stay below 1.5 degrees of global warming? An unscientific smokescreen.

A recent article in the Lancet (1) on the issue of decoupling GDP and CO2 emissions deserves our attention in order to better understand the subtleties of the discourses, methodologies and, to say the least, biased positivism of the concept of green growth. According to this study, Luxembourg is one of only 11 countries in the world to have achieved absolute decoupling between CO2 emissions and GDP between 2013 and 2019. In other words, they have succeeded in reducing their emissions while growing their GDP.

Yes, but...

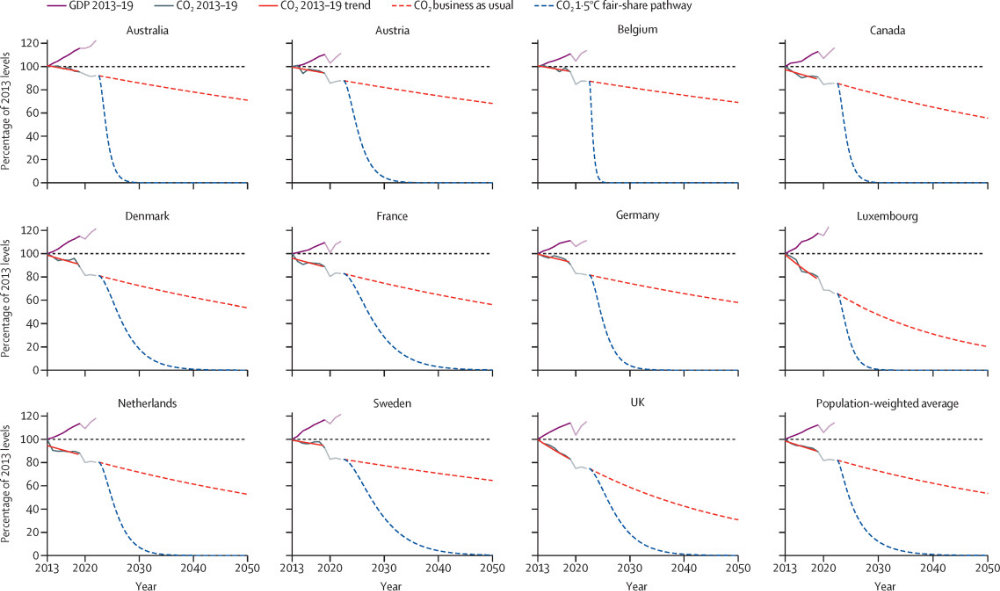

While decoupling has indeed taken place for this (very) small number of countries, it can in no way be considered sufficient, according to the authors, to attest to the practical success of hypothetical green growth. This is because the pace of decoupling is slow, excessively slow in relation to the objectives of the Paris Agreements and the remaining carbon budgets. Under no circumstances can these rates of decoupling enable us to achieve carbon neutrality within the allotted time: "the huge increase in the rate of decoupling required to meet the 1.5°C target appears empirically out of reach, even in the best-performing countries". At the current rate, these eleven champions would need an average of 220 years to achieve carbon neutrality. We are therefore a long way from a decarbonized 2050 horizon: "The rhetoric that celebrates the results of decoupling in high-income countries under the name of green growth is therefore misleading and represents a form of greenwashing."

Figure 1: In all high-income countries that have recently achieved absolute decoupling, the emissions reductions achieved fall far short of the emissions reductions required to meet their fair share of 1.5°C. (Lancet, 2023)

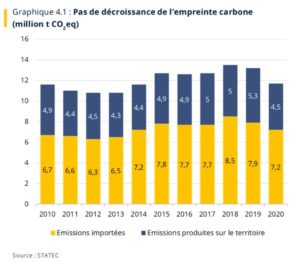

In its 2023 report, Simulation of the energy transition of the Luxembourg economy (2), STATEC, for its part, postulates that the Luxembourg economy is well on the way to achieving decoupling in terms of the PNEC (Plan national intégré en matière d'énergie et de climat): "the long-term projection shows a decarbonization trajectory similar to a "green growth" scenario, where direct emissions are decoupled from economic and demographic growth". The European methodology used excludes imported emissions and considers only emissions produced in the country (so-called direct). The Lancet study, on the other hand, takes into account all the emissions consumed by the country, i.e. including imported emissions. This is a much more realistic and responsible calculation of a country's CO2 impact, especially when it has a tertiary economy and imports the majority of its material goods and energy resources. The Lancet study also takes into account a fair distribution of the remaining CO2 quotas to avoid exceeding 1.5°C, in proportion not to the economic weight of countries but to their populations.. Statec settles for a sentence to solve the problem of importing emissions: "indirect imported emissions are the responsibility of the countries producing the imported goods". In other words, I'm not responsible the waste produced by my consumption if it comes from elsewhere. In Europe, however, 1/3 of the CO2 consumed is emitted by another geographical area of the world, and therefore passes under the European radar (3).. For Luxembourg, this ratio rises to 2/3. (3), (4)

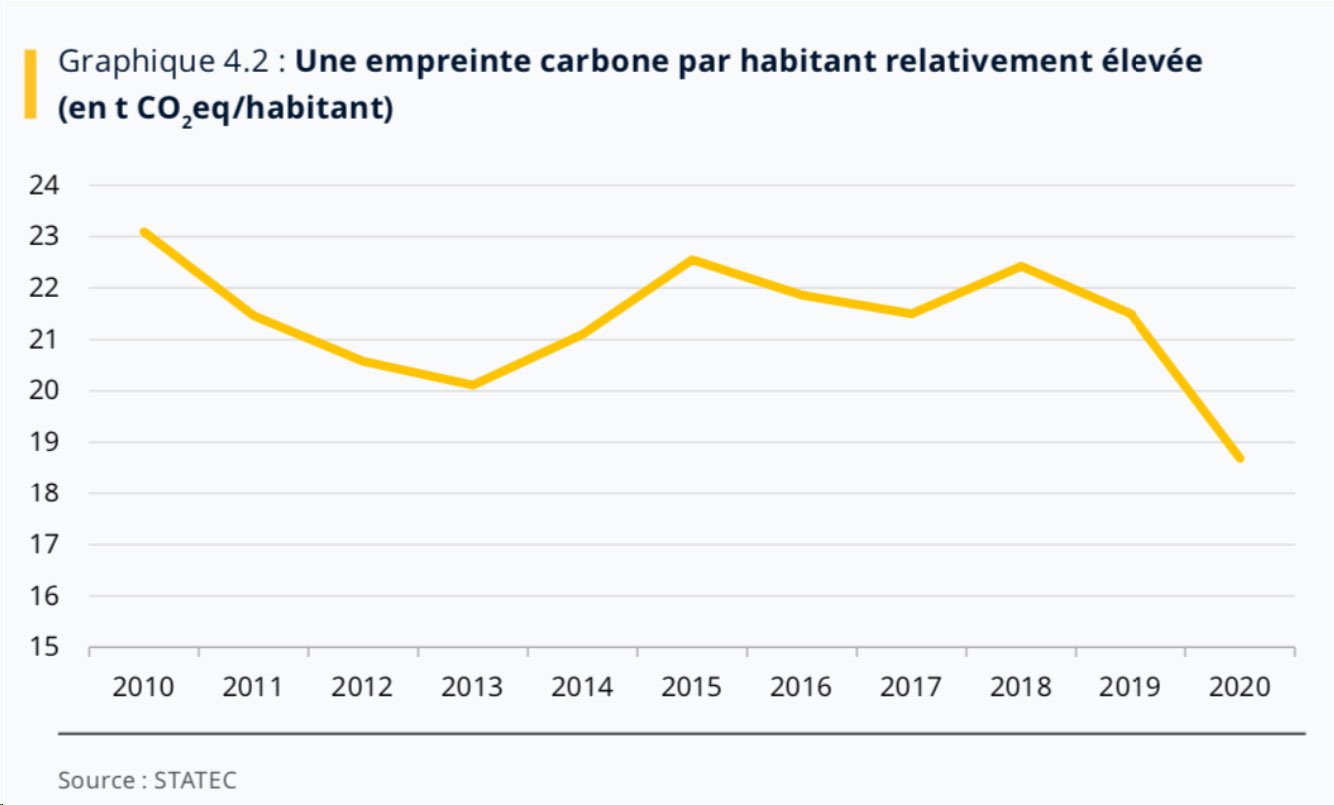

To solve the problem of our country's carbon neutrality in 2050, it's convenient to focus on just one third of our emissions. The fable of a carbon-neutral Europe in 2050 is based on this statistical sleight-of-hand. While we can't blame Statec for aligning itself with European methodologies, we regret that it does not follow the rigorous and coherent example of Sweden, which was the first country to take imported emissions into account, a complex but coherent task (5). This difference in methodology and use of figures means that we can boast of green growth when the physical reality contradicts the 1.5 degree objective. Of course, Statec is not fooled by Luxembourg's growing carbon footprint (which adds up the country's direct and indirect emissions). Nor of its carbon footprint per capita, which is not decreasing (excluding Covid). The graphs published in another note from 2023 bear witness to this, The environment in figures(4) In it, Statec admits that Luxembourg's carbon footprint will not decrease over the 2010-2020 period, and that there is no clear trend towards a reduction in per capita emissions (excluding Covid).

Statec's disconcerting optimism on energy efficiency fails to take into account the famous rebound effect

The rebound effect - whereby a gain in energy consumption will be cancelled out by additional consumption - although well documented (6), seems to be ignored by Statec. For the institute, Luxembourg's energy consumption will stagnate thanks to energy efficiency. And this despite economic and demographic growth: "Progress in efficiency, mainly due to electrification, would lead to stagnation in energy consumption, which would otherwise increase with sustained economic and demographic growth."(2) We won't develop the point of the rebound effect here, but we will illustrate it with the example used by researcher Victor Court (7). If we halve the amount of energy needed to travel 100 kilometers, will we still settle for the in-laws' vacation home? Or will we go 200 kilometers? Experience shows that it's the second option that's taken, whether the in-laws like it or not. All joking aside, this applies to all energy consumption, whether for transport, consumer goods, the size of heated areas, etc.

Energy efficiency is necessary to reduce CO2 emissions, but it cannot stand alone. It needs to be combined with uses and practices that aim for an absolute rather than relative reduction in energy consumption, CO2 emissions and material consumption.

Unfortunately, in its aforementioned report, the Statec only mentions and considers decarbonization (renewable energies) and energy efficiency (technological gains) as levers for the energy transition. And this at a time when a growing number of leading players (e.g. IPCC, International Energy Agency, European Union) are asserting that these two levers alone will not suffice, and that we need to take action. that it is urgently necessary to implement policies to reduce energy consumption through changes in behavior and organization, measures that can be grouped under the heading of sobriety (suffizienz in German, sufficiency in English).

It is regrettable that the Statec does not take these measures (of which a few timid examples are to be found in the PNEC) into account in its projections, thus failing to draw up a roadmap that is realistic in terms of carbon neutrality and relevant in terms of economic robustness.

This is also the path indicated by the Lancet study, which points out in passing that some of the hypotheses chosen for the study are not even the most pessimistic. The authors suggest a possible solution based on the concepts of post-growth or sobriety.

Countries' current approach rich is considered obsolete, fallacious in its account and scientifically unprovable..

The conference Beyond Growth which took place in Brussels in May 2023, with the notable presence of Ursula Von der Leyen, is a signal, let's hope, of an overcoming of political short-termism and a rethinking of development objectives. We urge the public authorities, and Statec in particular, to focus their attention on these essential elements to ensure that Luxembourg takes a leading and forward-looking role in the ecological transition, in order to anticipate adaptation and develop a solid, resilient and sustainable economy. Economic and strategic gains are also possible through these approaches, as we will outline in a forthcoming article.

References :

(1) Lancet, Is green growth happening? An empirical analysis of achieved versus Paris-compliant CO2-GDP decoupling in high-income countries, 2023 : https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(23)00174-2/fulltext

(2) Statec, Simulation of the energy transition of the Luxembourg economy, 2023 : https://statistiques.public.lu/fr/publications/series/analyses/2023/analyses-03-23.html

(3) Insee, Un tiers de l'empreinte carbone de l'Union européenne est dû à ses importations : https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/6474294#tableau-figure7

(4) Statec, The environment in figures, 2023 : https://statistiques.public.lu/fr/publications/series/en-chiffres/2023/env-en-chiffres-2023.html

(5) Special Report 18/2023: The European Union's climate and energy objectives - Contract fulfilled for 2020, but a guarded prognosis for the 2030 targets: https://www.eca.europa.eu/fr/publications/SR-2023-18

4691 views

0 comments